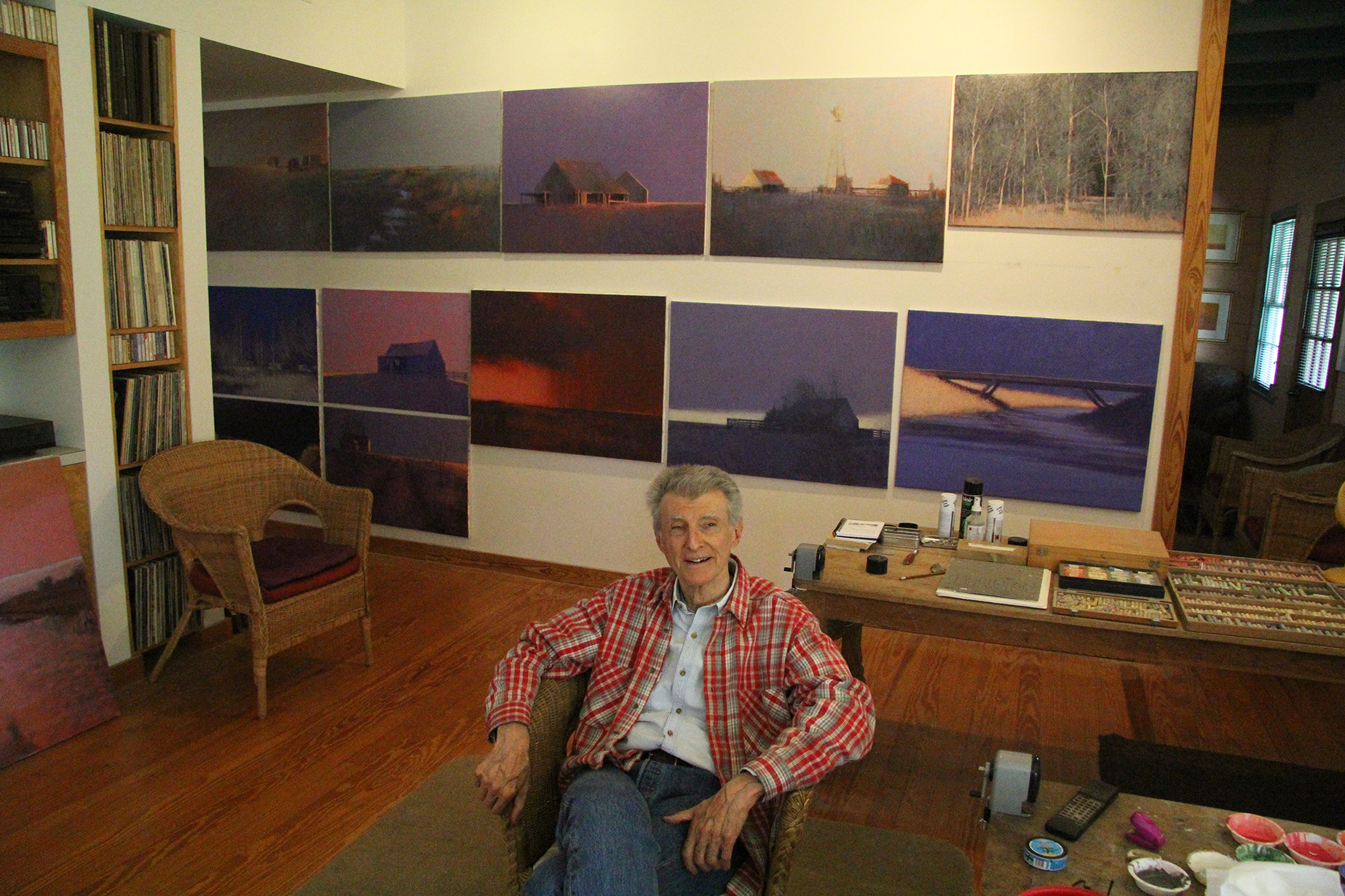

In the artist’s studio

By Linda Stall Special to the Fayette County Record

I arrived at William Anzalone's home near Round Top on one of the last cold rainy days of spring.

It is intriguing to visit an artist's studio. To visit Anzalone's studio is a particular privilege. He doesn't like to do interviews; in fact he said he usually declines. I knew that, even before asking, as I was able to find only two interviews with him in the last decade. He granted this interview as a favor to Joan and Jerry Jerring, owners of the Red & White Gallery where he will exhibit a collection of his recent work beginning May 11th. I told Anzalone that most of the press references I was able to find were articles about former students of his being interviewed about their own work, a fact that pleased him. It was clear from our conversation that he enjoyed his decades of teaching. And after an hour in his studio, I envied those students. Anzalone was educated in Brooklyn public schools, and there are still traces of Brooklyn in his voice. He graduated from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1958 with a degree in Architecture.

In 1960 he moved his family to Houston and began teaching art at the University of Houston, utilizing his skill in architecture to teach 3-D design, foundation drawing, and figurative drawing for 30 years. His own work has included figurative drawing and abstracts, but in recent years he has become known for his vivid landscapes of rural Texas

The Studio

Mr. Anzalone ushers me into the house just before the rain arrives. The house is dark, but the studio brightly lit, stark white walls, tables filled with jars of brushes.

The painting he is working on as I arrive is hung on a wall surrounded by soft paint splatters which tell of years painting in that same spot. The piece is predominately blues, soft and cool. On the long wall apposite are more works in progress, startlingly vibrant with rich red hues and very different from the icy coolness of the first. But they are not finished, "they won't stay like that," he says, it's "just the point they are at."

...I turn my attention back to the unfinished canvases. The images seem familiar, but I can't place them. They are the country landscapes Anzalone is known for. Trees and barns; hay bales and fields; our local landscapes which Anzalone portrays in his own distinctive style. Initially, he captures the scene using his digital camera. One painting is the result of an image he captured on a day so cold he wasn't sure the camera would even work. He prints his photos on his home printer, but only in black and white, he explains. The color comes from his imagination, creating the image that he wants to see. The photograph is just the beginning. He may move a tree, change a roofline, or develop the background to add depth and distance. He describes a process of capturing the image, manipulating the elements, and then as he puts it "the belly takes over and hopefully a painting results," and in the end "the place looks like it's supposed to."

He rejects the idea of duplicating a photograph onto the canvas, as though the closer the painting looks to the photograph the better the artist. "If the photograph is any good, then why paint it?" he said. What Anzalone portrays is "grounded in reality: he says, "this exists, but this is my take on it."

Through the Window

Pinned up on the wall behind Anzalone is a grouping of pastels, views through a window, which remind me of the small pastels chosen for the Red & White Gallery exhibit. I like the sunset, I say, and he corrects me, "it's not a sunset, oh, it could be, but it could be a sunrise, too," challenging me not to assume. The small pastels with their views through the windows are lovely, "but unrealistic" says Anzalone, "your eye will never see this." He explains that the window frame is in perfect focus, and so is the view beyond. But our eyes don't really work that way. The eye will focus on the window frame, but the landscape beyond will blur. He compels me to look out the studio window and verify that it is true, unlike the pastels, I cannot see both the frame and the view in focus at the same time.

Stuck in the Painting

While we have been talking, the exhibit paintings have piqued my curiosity. I want to see just one, and have him tell me about it. He removes the blue oil he has been working on and from the wall and sets it aside. He chooses a large painting titled "My First Cactus." Not that it is a painting of cactus, he explains, but it is his first painting to include a cactus. Like most of his paintings I have seen, it is the color that strikes the viewer first. Vivid blues, reds and oranges. There are trees, and a barn. The sky glows red and orange. But Anzalone wants you to see more. He wants to draw you in. He says "most people look at landscapes and say 'that's pretty' and move onto the next." He wants to "extend the time that a person spends with the painting," he wants the viewer "stuck in the painting."

He directs my attention to subtle vertical and horizontal lines that appear in "My First Cactus." Lines that mimic the look of a window frame, but here he uses them to alter space, rather than frame it. One horizontal line crosses in front of another. The two trees would otherwise seem to be on the same plane, but the "window frame" alters the space and moves one forward and the other back. The window frames "fade in and out" Anzalone explains, "playing with the dimensions." My attention returns to the rows of unfinished paintings hanging on the wall to my left. Before I had seen just the barns and the trees, but I now see the window frames everywhere. And Mr. Anzalone has succeeded, because I must stay with those paintings longer and find the frames, and trace their affect as they visually move the objects in the landscape into the foreground or away into the background. It is a play within the space that is riveting, and I am stuck.

__________________________