William Anzalone

the shapes and shadows of memory

by Jerrell Bullis

Southwest Art Magazine, March 1982

When William Anzalone gave up architecture — only three years out of M.I.T. — and moved south to Houston to become a painter, he had no idea that his future would be dominated by the human figure, in particular the female figure. He began painting with almost no training in art, for two years experimented with non-figurative styles, and then realized that his work was becoming more and more involved with the female form. Now, twenty-two years after that beginning, his paintings deal with a narrow range of subjects: one woman, two, sometimes also a dog. There is magic in the human figure, but Anzalone’s conjuring art evokes much more than the usually solitary female figure that focuses his oils and pastels.

“…I want it to be real enough so that people don’t question me about it, but I want it to be abstract enough so that they know that it’s not totally real.”

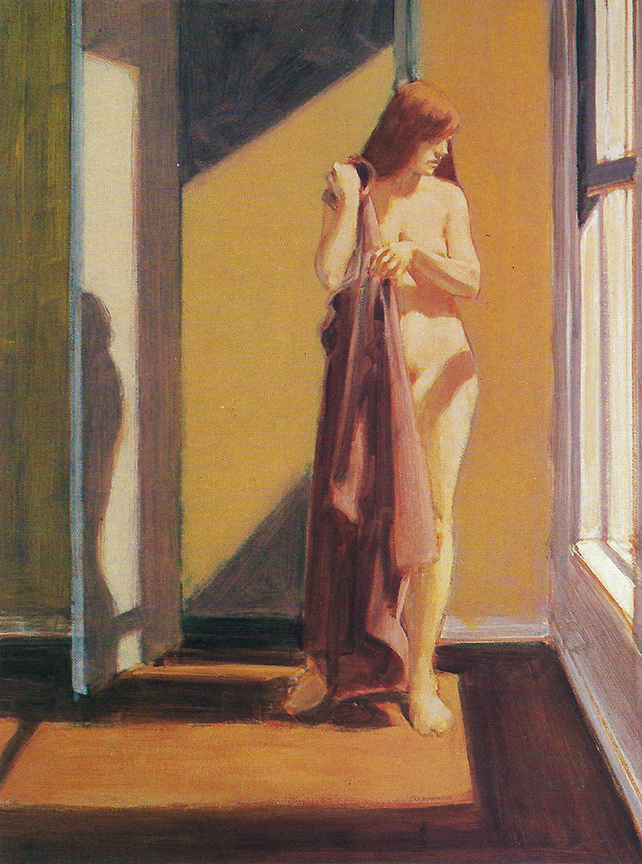

UNTITLED (1979), oil, 60 x 48

Anzalone, his wife, and his daughter moved to Houston in 1959. Two years working as an architect taught the Brooklyn native that he did not want to work in an office. So his interest shifted to painting, just as it had earlier moved from metallurgy to architecture. “Architecture was to metallurgy what painting was to architecture,” he explains. “It was just one step toward individualizing what I thought I wanted to do. If you go into pure creation, it has to be in the arts.”

A friend from college had mentioned a garage apartment Anzalone and his family could live in while he painted, so they headed south with their possessions — about $700 and two or three suitcases. They reached Houston and the garage, only to find that, while the garage was real, the apartment existed only in his friend’s imagination. After three months were spent trying to fix up the garage, Anzalone — now down to about $10 — found a small apartment and a job teaching part-time in the art department of the University of Houston. He also began painting.

“I just started painting,” he remembers. “It seemed like a reasonable thing to do. It was just trying this and that, because I had no formal education in art. I never went to art school, and I had no idea, other than what historical information I had, as to what an artist really is. I took a brief art history course in college, but it was mainly about architecture rather than art. We just started buying [art] books and looking around and going to galleries. Eventually I fixed on the figure because I saw that that was what I was usually doing.”

Anzalone did some “non-figurative” painting since “that was what freedom meant. It was the thing to do,” he recalls. Finally, however, the young artist decided that non-figurative painting was, in the end, decorative, and his attention turned to the idea of form in figure painting. His training in architecture helped, giving him “at least a degree of organizational ability.” Just as important, be began to pay more attention to the past.

“If you look at the history of art for 2,000 years,” he says, careful to add that he means Western art, “there was a direct line for 1,900 of thouse 2,000 years. It is a straight line, where one thing is added to another, like a stack of blocks, one on top of the other.” At the end of the last century, however, painting began to follow many different, experimental paths. Most of those, Anzalone thinks, have reached dead ends: “Pop art was a major event but it ended; abstract expressionism is a major event that ended,” he says. As all these “answers” to the question of the future of art appeared, traditional figurative art was submerged, alive but not attracting much attention.

“Young artists and students are drawn to those alternate paths,” the college professor says. The mentality of the art world today encourages young artists to search for “some clean idea that nobody’s trampled all up yet and to use that as their way into the art world. I far prefer to say that I work with ideas that people have been working with for thousands of years. I’m not going to try to do anything new [to that tradition] — I’m just an individual working within it, and the result has to be different because I’m different from anyone else.”

Just because the concept of change is no issue for him does not mean that his work has been static. In fact it has not been confined completely to figure painting. Only a few years ago he began to move away from the idea of an organization which focuses on an object in the canvas. “I tried to have a surface focus,” he says. A series of circus paintings resulted. Tent posts, ropes and lines, trapeze artists and their suspended equipment, seen from a distant viewpoint, form various geometric patterns on the canvas. The paintings are interesting, but Anzalone found them another dead end.

A principle reason for Anzalone’s dissatisfaction with the circus paintings is his feeling that too much of what goes into non-figurative painting is arbitrary. “I don’t like arbitrary things in paintings, “ he says. “It comes down to the fact that I don’t like to put a mark over there and then say ‘That’s a nice mark, I’ll leave it there.’ There is nothing arbitrary about the length of an arm. Either the arm is the right length for the body, or it’s wrong.”

Getting the figure correct is the least of Anzalone’s worries. He expends most of his energy trying to achieve a sound form for the picture as a composition , using the female figure as his focus. “I spend most of my time pushing things around in the picture,” he says. “The figure is never the problem that I have; it’s getting the damned environment to fit so that I have essentially a unit.”

Although he completes three or four paintings per month, on the average each is painted several times. He likes to complete a picture in one session and refuses to spend time tinkering with details. “What I do usually when I am painting is get lost,” he says. “I try to finish the picture each time I work on it, but I never succeed; it’s one of those things. Every time I paint it and I finish with it, I never like it. I mean I like it for a second, and then I think, ‘Oh God, that’s wrong and that’s wrong and that’s wrong.’”

Instead of trying to doctor the picture, he selects a color, mixes it with turpentine, and wipes the canvas down with a rag. The technique is helpful: “That tends to lighten the dark areas and darken the light areas, but I can still see the essential picture there,” Anzalone says. Then I start repainting it. But I have to do that from scratch. So the next time I pick it up, rather than just fiddle with the picture, I just start the whole damned thing again.”

The effect on his style is major. Although his figures and their environment are clearly realistic, thay are not highly detailed. The figures are well-rounded and the rooms have depth, but the walls and bulky pieces of furniture are plain and tend to be more important for their color and position than for their detail. Largely because of the repeated wipe-downs in the progress of the painting, one color usually becomes predominant. While his colors gain extra highlights by being put on in layers, the tones are muted and become important most of all for their evocative qualities: The suggestion of meditation present in many of the paintings comes not from the figure’s actions or positions, but from the subtle range of tones in the colors, which gives the paintings the atmosphere of being remembered. Even though Anzalone works consciously to have his figures frozen but not posed — as though caught not in motion, but at the moment before motion begins — the result is less suggestive of a photograph than of memory.

Also contributing to that quality in Anzalone’s picture is the degree of reality that the artist has chosen to work with. “There’s no horizon in the pictures,” he explains, “but there is a feeling that things are placed level with the figure. There is a sense of light that comes in that has to be the same on the figure that is it on the other objects. So, in essence, the pictures are abstract to me since I don’t copy photographs, but they are also real because I have a set of relationships that I have to deal with sooner or later. I like the fact that there is both a tangible nature to the reality of the situation and the intangible that I can make these things any kind of interior space I want. The shadow has to be there because I want it to be real enough so that people don’t question me about it, but I want it to be abstract enough so that they know that it’s not totally real. I’m not out to paint a realistic chair or a realistic table; I’m merely out to paint a believable environment.”

His concern these days is something very traditional in nature and very technical. “I do not like the horizontal planes,” he says. “But I tend to use them more and more to get the figure farther back in the canvas. What I would like to do is cut the figure off at the knees, but still have it appear to be immersed in the paint of the canvas. I’ve tried it an I’ve tried it and I’ve tried it ... I may have succeeded in doing it at times but I can’t point to a specific time and say ‘I did it there.’ Each one of these pictures to me is a monstrous failure.” he says, gesturing to the paintings-in-progress on the walls of his large, all-white studio. “I keep painting them and painting them as best I can, and I don’t quite know how to deal with the problem. I can put an object in front of the model to set the figure in space, but I simple cannot get that figure back in the canvas without relying on the floor surface or some physical device to do it.”

Anzalone’s work has been associated with Meredith Long & Co. in Houston for more than twenty years and has been displayed throughout Texas, Massachusetts, New York City, and in several cities in Mexico. It is present in several dozen collections. In 1980 he became a full professor in the art department of the University of Houston. And the quiet, pensive figures in his paintings — a woman fastening her shoe or putting cans on the kitchen shelf, a nude standing alone in an empty space of a brown canvas — show that Anzalone has found the slightly submerged but sound foundation he was looking for in the 2,000-year tradition of Western art. ¶

Immersed in the

Landscape

by Virginia Campbell

Southwest Art Magazine, February 2006

WILLIAM ANZALONE’S LANDSCAPES REFLECT A TEXAS TERRAIN THAT ENTRANCES HIM MORE EACH PASSING DAY

A LITTLE MORAN (2006), oil, 16 x 20

It shouldn’t be particularly interesting to note that a certain painter draws well. Drawing is one of those basic skills you figure every artist had better have down. Still, unimaginable as it might have been at the turn of the century for a painter to consider drawing superfluous, by the mid-20th century a great many did, and at the turn of the 21st century — by which time many artists had long deemed painting itself irrelevant—there were a surprisingly large number of painters who probably couldn’t doodle their way around a cocktail napkin.

So it is actually worth noting that the Texas painter William Anzalone draws very well, both with oil paint and with pastel. He draws so beautifully, in fact, that he can make fields of long grass and stands of bare trees — his frequent subjects—testaments to how visually compelling the natural world is in even its least dramatic aspect. Other qualities of his work stand out, too. His compositions, while capturing the lovely superficial randomness of flora and topography, are so reticently convincing that you feel you are getting glimpses of some ultimate, invisible order. His layers of transparent paint often building into radiance that makes it seem like the earth is glowing, rather than merely bathing, in the sun’s light. And his odd complementary color couplings — far more yellows against lavenders than reds against greens — give his landscapes unexpected, elusive emotion.

You could justifiably assume that Anzalone’s curiosity and ambition are what drive his clear preference for the patterns and perspective of fall, winter, and spring landscape over the opaque luxuries of summer. But there’s another, equally important factor, one that is — pardon the pun — out of left field: snakes. Anzalone lives in a small, rural town between Houston and Austin, where the obvious vexations of summer heat and humidity are trumped — at least for him — by the menace of water moccasins.

“I don’t like snakes,” the artist declares. By no means a plein-air painter in any case, Anzalone is, he goes on to disclose, loath to venture into nature during the season of heavy foliage even so far as to walk across a field. “If I’m gonna get myself bit, I’m gonna know what bit me,” he explains, warming to his topic. “When I’m working in grass near water, I’m nevous. Water moccasins are aggressive — they’ll come get you. I never sit down on logs. And I carry a 38 loaded with rat shot. I’m scared. Cowards are careful. I’m very careful. So far I haven’t been bit.

Inasmuch as Anzalone was born in 1926 and has never been molested by a reptile yet, his mini-diatribe about water moccasins makes it tough to keep a straight face. Now imagine all this said in a Brooklyn accen that half a century of Texas living hasn’t blunted. (Anzalone sounds like a non-whiny Woody Allen — with whom, in fact, he went to high school in Flatbush.) The cognitive dissonance produced by trying to reconcile the quiet, almost Asian subtlety of Anzalone’s most recent landscapes with the inflected verbal energy of his conversation has a pleasant, comic edge to it that’s ultimately instructive. Restless imaginations over long stretches of time become more, rather than less, unpredictable.

Anzalone grew up in his Brooklyn neighborhood with a talent for mathematics and physics that an uncle, with whom he was closer than he was to his own father, encouraged. Becaiuse his uncle was an engineer, the young Anzalone aimed himself in that direction and headed to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Boston for college. He had, at this point, no inclination toward art. But once fully acquainted with the nitty-gritty of engineering, he switched to architecture, which led to drawing and painting classes. The seed that grew later into his art career was planted in a lecture course given by an especially brilliant professor who, taking a broad view of architecture, examined how the eye interprets visual information to conceive a three-dimensional world, and how three-dimensional space was represented in art before and after the discovery of perspective.

It was during this time that Anzalone began looking at painting with new eyes, and being in Boston gave him rich opportunities to see masterpieces. The one that knocked his aesthetic socks off was Gauguin’s great (and largest) painting, WHERE DO WE COME FROM? WHAT ARE WE? WHERE ARE WE GOING? You detect the influence of this experience on Anzalone’s way of seeing, particularly in his use of color, right up to taday in pictures like A LITTLE MORAN.

When he graduated from MIT, Anzalone was already married and the father of a baby daughter. If it had entered his mind to become an artist, he was in no position to act on the idea. Instead, he took a job at a small architectural firm on Cape Cod and spent the next year drafting plans for summer homes for the wealthy seasonal population of the Cape. During that time he did figure drawings and nonobjective paintings in acrylics on paper. At that point, for no particular reason, a friend who lived in Houston called up and suggested he come to Houston to paint. With his wife and daughter, he did exactly that. “I do strange things,” says Anzalone, “and that was one of the strangest.”

Houston in the 1950s was much farther away from New York and New England than it is now, and it was a smaller, looser place, too. “Every gallery in Boston would have thrown me out,” says Anzalone, “but Meredith Long took me on.” Long has remained Anzalone’s representation for half a century. “I listened to him,” says Anzalone, “and he’s never interfered with my work.” Long might have wanted to interfere, though, when Anzalone abandoned his abstract images for representational painting. “I had 20-some people waiting for my nonobjective paintings, and I was painting figures. I’d decided that’s where I wanted to go. Nonobjective painting seemed to me to be a dead-end street.” Anzalone hasn’t looked back since then. “I agreed with [the painter] Francis Bacon, who said nonobjective painting is basically decorative. Nonobjective paintings are nice. I can admire them. Hang ‘em over the couch. But I don’t get worked up by them.”

Shortly after establishing himself in Houston, Anzalone, armed with his background in architecture and a degree from MIT, was offered a teaching position at the University of Houston, where he remained a faculty member until 1993. “I was at the right place at the right time,” says the artist of the freedom that a university job afforded him. “It gave me the opportunity to paint a lot of bad pictures and not show them to anybody.” Houston also provided an environment that was, according to Anzalone, vibrant and interesting for artists. The major contemporary artist Julian Schabel was one of Anzalone’s students: “He was already Julian Schnabel when he walked in the door,” says Anzalone of the student who became a superstar in the 1980s. “The only thing we could take credit for at the universioty was that we didn’t screw him up entirely.”

Though teaching created financial security and a pleasing community for Anzalone, it had a downside, too. “I was a natural teacher, and I liked it,” he says. “I like people. But teaching is not a good way to support yourself as a painter if you’re serious about teaching, which I was. The intellectual demands of teaching are rigorous, and you have to stay up to date with what’s going on in the art worls. It affected my work — my figures began to get too realistic. You begin to ask, ‘Am I using my gut or my brain? I never got to where I wanted to get while I was teaching? It wouldn’t have taken me as long to get to the work I a doing now if I hadn’t taught all the time.”

Paintings done over the 12 years since Anzalone retired are a marked departure from his previous work. His work today acknowledges both tonalism and Impressionism, as well as the post-Impressionist experiments with color. “The kind of paintings I do now were more the oddity than the direction before,” he says. Landscape, which he only started doing in the ‘80s, has taken over as his primary interest. He explains, “I started going out to sketch, using a small spiral pad and ballpoint pen. You can’t climb over the barbed-wire fences carrying a lot of stuff with you. I’ll do the same sketch three or four times with different light. I have a good visual memory, and probably 50 percent of what’s in a painting is remembered. I blank out names, but if I’ve seen something, I remember it.”

Having achieved his ideal working conditions only late in life, Anzalone is intent on keeping his creativity going, which means maintaining his health and strength. “I started running at 40,” he says. “I run three or four times a week, and I lift weights three or four times a week. I don’t want to end up having to use a walker. I admit I’m a fanatic about fitness — it would be a lie if I said I wasn’t. In fact, I’m fanatical about everything I do that I’m passionate about.” That probably explains why, until he recently added a studio unto his home, he unashamedly laid claim to whatever space in the house he wanted for painting. “I always took the best room for my studio, usually the living room,: he chuckles. “I needed it!”

You can see in Anzalone’s current paintings how all the aspects of his life have been brought together in a way that gives full power to his well-seasoned gifts. “Life has been very kind, and I’ve enjoyed it,” he says simply, and you can aee that perspective in his work, too. The painting PICKING is a great example: “We had just built a new kitchen with casement windows that opened out on the garden, and one day I saw my wife out there deadheading blossoms in her huge rose garden. I’d done ‘self-portraits’ by painting my glasses. Since the minute you paint representationally you start confronting the issue of painting verses photography, I once painted a ‘self-portrait’ in which my glasses were facing down a camera. So when I saw this scene out the window, I thought, ‘Why can’t the window be the same as my glasses?’” With this in mind, Anzalone created a picture that shows the frame of the opened casement window and, beyond, a woman’s figure with arms upraised in a manner that certainly can be understood to be cutting roses, but at the same time can seem to be a reaching out into some magical beauty. The painting thus celebrates both the way we see the world, — though interpretive perceptual grids represented by the window — and the way we feel it, through the delicious immersion of our excited senses.

Self-admitted happy fanatic that he is, Anzalone starts work at 7 every morning and spends most of his time doing nothing else. “Besides getting invited out once in a while for a meal,” he says, “I paint. That’s all I do.” ¶